Katarzyna Cantarero on promoting meaning at work

Katarzyna Cantarero completed her PhD in 2015 at the Institute of Psychology, Polish Academy of Sciences. She received funding from National Science Center in Poland, and the National Academy for Academic Exchange in Poland funded a 1-year postdoctoral scholarship at the University of Essex. Kasia researched different meaning interventions designed to boost work engagement. She also studies moral judgment and behavior with a special interest in lying. In 2018, she received the Robert Zajonc Award for Young Researchers (Polish Social Psychological Society); in 2022, together with Monika Wrobel and Katarzyna Jasko, she became Co-Editor-in-Chief of a free of charge, open access journal called Social Psychological Bulletin.

Kasia on the web: SWPS | Twitter | Research Gate | Google Scholar

By Kenneth Vail, Cleveland State University. December 1, 2022.

ISSEP: How did you first become aware of and interested in existentialism and existential psychology?

Kasia Cantarero: As a PhD student I applied to the workshop on morality at the EASP Summer School that took place at the University of Limerick in 2012. I didn’t get into that workshop, but my second choice was the workshop titled “When is life meaningful? Social cognitive processes underlying meaninglessness and meaningfulness.” I didn’t know very much about the topic, but I thought it might be interesting. It turns out that meaning workshop was a life-changing experience. I studied with excellent teachers, Eric Igou and Leonard Martin, who guided me through the literature, gave thought provoking questions, and helped me in finding and polishing interesting research ideas. That workshop was so stimulating; it really sparked my interest in existential psychology. That was also where I began collaborating with Wijnand van Tilburg, in which we translated our ideas about meaningful work into a variety of productive studies.

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some great work leveraging existential psychology for meaning and engagement at work. Can you tell us more about that research?

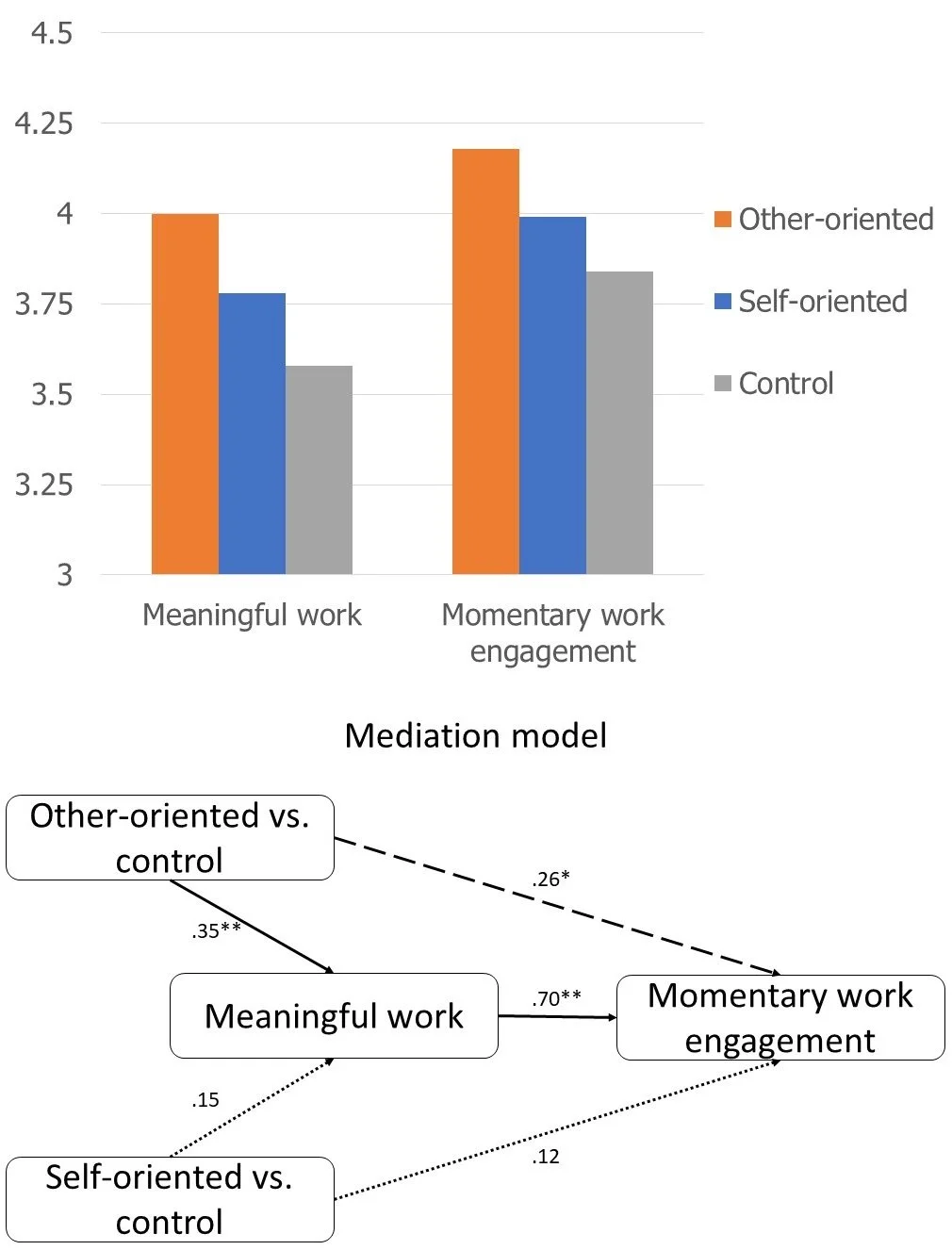

Kasia Cantarero: Sure! Together with Wijnand van Tilburg and Ewelina Smoktunowicz, I was interested in testing whether it was possible for brief interventions to, at least momentarily, boost the preception of meaning and engagement with one’s work. Additionally, based on previous research we knew that there are many sources of meaningful work that could, essentially, be divided into two broad categories: self-benefitting (e.g., advancing one’s personal career) and other-benefitting (e.g., helping others). So we were also interested in testing whether meaning and engagement at work are, potentially, more strongly impacted by self-oriented vs. other-oriented interventions.

In one of our studies, we recruited 254 workers and used a between-subjects experimental design to randomly assign them to one of three intervention conditions:

Control condition: Participants were asked to briefly tell us about the equipment they use at work.

Self-oriented condition: Participants were asked to tell us how their work allows them to advance in their career.

Other-oriented condition: Participants were asked to tell us how their work served the greater good.

All participants in each of these three conditions were then asked to indicate how meaningful they felt their work was, using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree) on the following three items:

The work I do is very important.

My job activities are personally meaningful.

The work I do is meaningful.

We also asked participants to similarly rate their momentary work engagement on the following three items:

Today, I feel bursting with energy at my job.

Today, my job inspires me.

Today, I am immersed in my work.

Data patterns indicated that, compared to both the control condition and the self-oriented prompt, the other-oriented intervention prompt led to increased perception of meaning at work which, in turn, was associated with greater momentary work engagement.

ISSEP: How did you develop your interests in that topic area?

Kasia Cantarero: Well, before I entered academia, I spent several years working a sales job. My coworkers and boss were nice, but I just didn’t find the work meaningful. I’m sure other people found it meaningful, but I didn’t. Whether I sold one more thing, or one less thing, it just didn’t seem like it made a difference or contributed anything of value into the world. And that’s important, because our work is an extremely significant portion of our lives—most of us spend the majority of our waking hours doing our jobs. So, I decided I didn’t want to spend my life doing that sort of work anymore. Instead, I circled back to academia because I wanted to help learn more about our working lives, and how moral values and perceptions of meaning impact our willingness to engage our jobs.

The traditional path for a lot of academics is that they go through primary and secondary school, then matriculate into their undergraduate, then graduate school, and then they enter the academy. But unless something extraordinary happens along the way, they don’t really get first-hand experience out in the real world along with everyone else. It’s just classroom experiences and ivory tower. So I think it was to my advantage to have had real-world work experiences, with years working in office jobs, as it provides empathic insights about most people’s day-to-day life. And that’s kind of the whole point of psychological science. We don’t do lab studies, for example, because we’re interested in the lab for its own sake; we do lab studies to help us better understand what happens out in the real world—so I think it’s a real advantage to have real-world work experiences along with my academic research training.

ISSEP: In what ways can your work help us better understand important experiences and events?

Kasia Cantarero: Some illustrative examples could be seen during the pandemic. During the pandemic, a lot of people looked at what they were doing with their lives and asked themselves “Is this worth it?” A lot of people in “menial” rank-and-file jobs—such as warehouse workers, fast food staff—decided it wasn’t worth it and quit, creating an employment shift some called the Great Resignation. Not everyone did that, of course, and it’s difficult to know everyone’s motivation in those circumstances, but in light of our research one possibility is that during the pandemic many of these folks did not think that shipping a few extra packages or working the fast food drive-thru was really contributing to the greater good. They didn’t see it as particularly other-oriented work, which we know from our research means they likely didn’t view it as particularly meaningful work that was worth doing. At the other end of the spectrum, during the pandemic we heard so many inspiring stories of frontline healthcare workers—who do a job that is very other-oriented—remaining passionately engaged in their work despite being paid poorly or not at all and entailing significant risks. Perhaps the natural other-orientation of healthcare helped those front-liners feel their work was particularly meaningful, which helped to fuel their commitment to their jobs.

ISSEP: Do you see any interesting connections between your research and other material in pop culture?

Kasia Cantarero: Oh there are lots of great examples; I can tell you about some of my own personal favorites, and some that others have pointed out to me when they hear about my work.

One of my favorite examples comes from the TV series Friends. One recurring theme in the show is that Chandler and Monica are each striving to find meaningful work. In one episode, Chandler quit his job, despite being offered promotion, because he didn’t find it more broadly meaningful. Monica, on the other hand, got a job in a restaurant and was willing to suffer uncomfortable attire because she found the work particularly meaningful.

Another set of examples stems directly from the classic existentialist literature produced after WWII, exploring existentialist concepts in the workplace. One is The Organization Man (1956), by William Whyte, which was a non-fiction analysis, in part, of the shift in attention from world war to the corporate world. So many people understood the war effort through a moral lens, as good vs. evil; one’s efforts were toward the greater good—to defend the freedom, lives, and livelihoods of entire nations of other people. And once it was all over, many of the men and women who were participating in it just… went back to their work and sold vacuum cleaners or whatever else. Whyte’s thesis in The Organization Man was that it became difficult for individuals to find meaning again in these sorts of individualistic pursuits, so in collectivistic ways they began to find meaning by serving organizations. Around the same time, Sloan Wilson’s novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1955)— and the similarly-titled film (1956) starring Gregory Peck, Jennifer Jones, and Fredric March—also identified that people often returned from the war to find less meaningful lives, by comparison. Wilson similarly explored the idea that some people found other-oriented meaning in serving corporate organizations, others found it with family, and some struggled to strike a satisfying work-family balance.

A final example comes from the animated series The Simpsons. A long-standing thread in the series is that Homer has a good job doing quality control at the nuclear power plant. After his initial enthusiasm, the job turned tedious (mostly just monitoring gauges and hitting a few buttons) and he quickly ceased to find it personally meaningful. However, he found an other-oriented way to stay engaged: to provide for his daughter. In a rather heartwarming example, whereas Homer’s bosses had posted a sign reading “Don’t forget, you’re here forever,” Homer began to pin pictures of his daughter over the sign in such a way that it now read “Do it for her.” With that new other-oriented appraisal of the job, Homer found his work meaningful and (at least most of the time) was engaged with his job.

ISSEP: What do you see as the most important next steps in studying the role of existential issues in work-life satisfaction?

Kasia Cantarero: Now that we’ve documented the effects of brief interventions on momentary meaning and engagement at work, the next steps would be to explore the possibility of more involved interventions and longer lasting effects. Additionally, we’ve also begun exploring individual differences in need for sense-making and how it might relate to personal and professional functioning. So far, we’ve found that the need for sense-making relates positively to work engagement and presence of meaning in life.

ISSEP: You’ve attended, and presented research at, our Existential Psychology Preconferences; how has your experience been with those?

Kasia Cantarero: I resisted attending online conferences during the pandemic, so it was my first experience at an online conference and at the Existential Psychology Pre-conference. I really enjoyed it and was happy to attend; it was great to be able to be in my office here in Wroclaw while meeting with all these other researchers from around North America, Europe, and Asia. I particularly enjoyed Laura King’s talk about the research on meaning; it was inspiring and thought provoking. I also enjoyed the possibility to talk about research with other existential psychology researchers, exchange feedback, and make new connections.

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

“Find a good mentor that is an excellent researcher and ask a lot of questions.”

Kasia Cantarero: It’s hard to overestimate the role of a mentor. It’s helpful for amplifying the cumulative effect of science. Your mentor can help advise you based on past experiences; you can know about and avoid past mistakes, and know about and build upon prior successes. Find a good mentor that is an excellent researcher and ask a lot of questions.

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the research context?

Kasia Cantarero: Well, I am a long-distance runner and my favourite distance for regular runs is 10K. I also like learning languages; I’ve taken up Czech language last year and I really enjoy it! I have classes once a week, and I do the language apps in between. I’m a big fan of Czech beer and Czech literature (not necessarily in that order).

I’m a mom of two girls, age 7 and 9, and a new baby boy. My girls have just reached the age where they’re able to be a bit more independent. So during the pandemic, we could tell them mommy and daddy needed to work and they’d say okay and simply play with each other. We spent time together for meals, then we’d work while the girls played, and that made life just a bit more bearable. We wound up having five meals a day, but at least we could have some time to ourselves too. I also like reading novels. Once my girls reached that age where finding a work-life balance stopped being “mission impossible,” I could again turn to reading books unrelated to my work in my free time without feeling guilty and/or excessively tired. This is something that puts a smile on my face. This past summer, I read The Books of Jacob, by an amazing Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk. But now that I’ve had a new baby boy, work-life balance is back to being mission impossible!

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music in the lab; what are you listening to lately?

Kasia Cantarero: When I’m working, I need to be able to think my own thoughts. So during those times, I tend to listen to jazz style music. Lately, when I work I’m listening to a Jazz Divas compilation on YouTube with wonderful songs by Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Nina Simone and others. But when I go for runs, I tend to listen to more dynamic and energetic rock music, like Pink Floyd (especially the Dark Side of the Moon), Fleetwood Mac, and U2. My all-time favorite song is Seven Wonders, by Fleetwood Mac. I can never get bored of that song, and I love listening to it while working or running or any other time.

I’ve also got a bit of a music struggle in my house, because my kids tend to complain about any music that doesn’t come from their children’s movies. So when I play my own music, they complain that it’s boring, and say to turn it off. But sometimes their kids movies use songs that I like too. For example, Sing 2 used U2 songs, and Minions used songs by The Doors. So now my kids love those songs because they associate them with their movies, and I love those songs because it’s good music, so we can enjoy listening to those songs together.