Alexis Goad on Culture, Authenticity, & Indigenous Identity

Alexis Alexis Goad is a PhD student at the University of Arizona working on cultural-existential psychology with Dr. Daniel Sullivan. She earned her M.A. in Experimental Research Psychology from Cleveland State University while working with Dr. Kenneth Vail and earned her B.A. in Psychology from Oklahoma State University. Broadly, Alexis is interested in the effects of culture on existential concerns, such as the experiences of authenticity and suffering in the conceptualization of self and identity. Specifically, Alexis is interested in how the current sociopolitical landscape affects conceptualizations of American Indian identities and the role suffering plays in these identity narratives. Alexis’s research and scholarship has earned her awards from the Ernest Becker Foundation, the Regent’s Distinguished Scholarship, and the Osage Nation Scholarship.

Alexis on the web: UA Cultural-Existential Lab website

By Kenneth Vail, Cleveland State University. September 1, 2021.

ISSEP: How did you first become aware of and interested in existentialism and existential psychology?

Alexis Goad: Well, it certainly wasn’t taught in any of my undergraduate courses. I remember being a bit disillusioned with psychology, as an undergraduate, wondering whether it was for me and—if so—where I might fit into the field. One day I was in my advisor’s office, talking about some possibilities and she off-handedly mentioned ongoing research on terror management theory. I started reading about it that evening and found it quite interesting, but at the time it just didn’t work out. I applied to a bunch of PhD programs and didn’t get into any of them. I took a gap year and worked for an ophthalmologist, but I didn’t let those rejections get me down—I developed an even stronger desire to pursue a PhD in psychology. So I volunteered and built up some research experience, and applied to some Master’s level programs to get my foot in the door.

I got into Dr. Kenneth Vail’s lab, at Cleveland State University, and it was such an enriching experience. I learned so much more about terror management theory, of course, but also learned about a whole new world of perspectives in existential psychology. Our research touched on a variety of topics and he also taught courses on the Science of Existential Psychology where I learned about research on authenticity and self-determination, existential isolation, religion and spirituality, meaning in life, and identity. I had always been interested in political psychology, and identity and culture, but existential psychology offered an opportunity to really get at the deeper, more meaningful, and more fulfilling understandings of why people think, feel, and behave the way that they do.

Then I applied again to a variety of PhD programs with existential psychology research labs, with a specific focus on culture and identity. I got accepted into Dr. Daniel Sullivan’s lab, at University of Arizona. There, I’m researching culture and identity from an existential perspective—including the role of authenticity in people’s ideas about what to do, who to be, how, and why.

ISSEP: Your research is focused on culture and authenticity in Native American identity. Can you tell us more about those topics?

Alexis Goad: Of course! My research is focused on how exposure to different cultural representations of the Native American identity might impact people’s ability to internalize indigenous identities as part of their authentic self.

Clockwise from top left: Photograph of Lakota leader Sitting Bull (1883); George Catlin’s painting Buffalo hunt, chase (1844); Photograph of Lakota leader Red Cloud (c. 1880); George Catlin’s painting Sioux war council (1850).

Because North America has become populated by immigrants, being “American” isn’t particularly informative when it comes to race and ethnicity. So, we Americans often identify ourselves based on our racial or ethnic heritage—what sort of people were our ancestors? Were they Irish, Turkish, Japanese, “African” (about as specific as it gets for many descendants of slaves), or were they perhaps Native? This question is complicated, however, by the variety of different perspectives on the essential characteristics of any given race or ethnic tradition. If we think about the Native American identity, for example, we find at least two sources of such perspectives.

Non-indigenous views of Native American identities derive from outsider views. In mainstream American culture, such depictions are often rooted in the historical observations, stereotypes, and caricatures made by European Colonizers who either poorly understood and exoticized Native American peoples, at best, or were outright racist and hostile, at worst. School textbooks show old black/white photos of stern-faced Lakotas such as Sitting Bull, Red Cloud, and Crazy Horse; other media routinely depict “Indians” as the strong, silent, and one-dimensional noble savage—nomads who live in tipis, hunt buffalo with bow and arrow, smoke “peace pipes,” have a mystical connection to nature and animals, and of course always wear feathered war bonnets.

By contrast, an indigenous view of the essential characteristics of a Native American identity would derive from the contemporary lived experience within the culture (e.g., Arapahoe, Choctaw, Shoshone). Members of the contemporary Osage Nation, for example, might speak English as their first language, enjoy rock or hip hop music, belong to a Christian church, work as a statistician or software engineer, manage sophisticated energy and mineral rights contracts, and might even participate in the judicial, legislative, or executive branches of Osage government.

Contemporary Native Americans Phillip Martin (politician), Dia Molnar (U.S. Air Force), Harvey Pratt (forensic artist), Jamie Oxendine (author, performer), Joe Shirley Jr. (fmr President, Navajo Nation), Lori Piestewa (U.S. Army), Robbie Robertson (film composer, actor, author), Mary Kim Titla (journalist), and John Herrington (NASA astronaut).

The difference between the indigenous and non-indigenous views matters quite a lot when it comes to the felt authenticity of one’s own experience and identity. If a young woman is exposed to and internalizes the contemporary indigenous view of what it means to be Osage, and her lived experience aligns with that conceptualization, then she’ll likely identify as an authentic member of the Osage community. But if that same young woman is exposed to and internalizes non-indigenous views of Native identities (e.g., caricatures derived from European-American Colonizers), even though her lived experience remains the same, she might not consider her lived experience to strongly align with what she thinks it means to be Osage—and thus she likely wouldn’t consider herself to be authentically Osage.

ISSEP: How does your research bring those topics together?

Alexis Goad: My research brings these topics together in a three-prong approach. The first prong is to document the regional indigenous and non-indigenous views of the essential characteristics of Native cultures and identities. Here in Arizona, the major regional tribes are the Tohono O’odham, Pascua Yaqui, and Navajo. So, my team and I are working with local Indigenous-identified people (as colleagues, respecting tribal sovereignty and autonomy) to conduct mixed method research—both qualitative interviews as well as quantitative measures—to gather a full understanding of the contemporary indigenous view of what their tribal identities mean. We’re also doing similar data collection among the broader non-indigenous population (e.g., American Whites, Blacks, Asians) to document non-indigenous views of Native identity.

The second prong is to do cross-sectional research, among Native Americans, to quantitatively explore the relationships between (a) the internalization of indigenous vs. non-indigenous views of Native identity, (b) the similarity of their lived experiences to those views, and (c) their feelings of authenticity, self-concept clarity, physical and mental health, and sense of meaning and purpose in life. The third prong is to longitudinally track those variables over time among samples of Native Americans who grew up in tribal communities but then left, compared to those who grew up in non-indigenous communities but then moved to live among tribal communities.

ISSEP: In what ways can your research help us make sense of important human experiences, better understand important events, or inform our cultural or technological trends?

Alexis Goad: One trend has been the use of technology to promote the revitalization of indigenous cultural identities. For example, I’m Osage and was born and raised in Oklahoma, where many tribes were forcibly relocated as a result of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830. Because I grew up on tribal lands, surrounded by contemporary indigenous culture, I never questioned the authenticity of my Osage identity. However, when I left Oklahoma to pursue my master’s degree in Cleveland, Ohio, I found myself surrounded by people with non-indigenous, caricatured views of Native peoples – and even some people surprised to learn that Native Americans still existed.

Top left quarter: Oklahoma artist Yatika Starr Fields (Osage/Cherokee/Muscogee Creek) with Eternal Sun at the Oklahoma Contemporary. Top right quarter: Tocabe—An American Indian Eatery offers creative food inspired by Osage cuisine, including bbq buffalo ribs, fry bread tacos, and vegan plains grains salad bowls. Bottom half: The WahZhaZhe Ballet blends cultures and art forms into a vibrant and progressive presentation of modern Osage life.

However, the Osage Nation (and many other tribes) has been making great use of technology to expand its cultural availability. Even though I’m away from home, I’m still connected to my tribe on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, where I’m able to see indigenous representations of Osage people’s daily life. Comprehensive website outreach also makes it possible to keep in touch with the Osage government, cultural center and museums, and I’m even able to take Osage language courses over the web so I can continue to learn and speak Osage. This trend has made it easier for the various Native American diaspora—who no longer live on reservations—to continue to internalize contemporary Native identity as part of their authentic self.

Another trend is that companies such as 23andMe.com and Ancestry.com are now providing DNA testing services and claim to be able to identify the percentages of one’s specific geographic, racial, and ethnic backgrounds. Such tests are often used to help provide clues on one’s journey toward reconnecting with lost, stolen, or erased identities. But they’ve also led to controversies about racism, cultural appropriation, and gatekeeping, especially when their use seems to be based on the non-indigenous view that a certain percentage of blood lineage is the essential characteristic of Native identity—an idea which, itself, stems from discriminatory US Colonial “blood quantum” laws.

One high-profile example involved Sen. Elizabeth Warren. Warren is not a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, nor member of any Cherokee bands, nor did she ever live in any contemporary indigenous community, yet she repeatedly claimed to be Native American. When challenged about her Native identity, during her 2020 Presidential campaign, she took a DNA test which she claimed proved her Native identity. Criticism poured in. Her conservative opponents argued that she did not have enough “Indian blood” to claim Cherokee identity whereas Native tribespeople argued that authentic Native American identity involves lived experiences and established relationships, not simply the possession of particular DNA. Warren later apologized at a Native American forum for using the test this way.

ISSEP: You’ve been studying these issues using psychological science. Do you see your research topic being dealt with in interesting ways in the humanities or the arts?

Alexis Goad: Yes, I see at least three patterns in the ways Native American identity has been dealt with in the arts—film and television media, but also print, sculpture, theatre, and so on. Each bear important implications for the ways the general population, both indigenous and non-indigenous, understand what it means to be “authentically” Native American.

First, mainstream (non-indigenous) American media has historically failed to recognize and represent the daily lives of contemporary indigenous Americans—as doctors, lawyers, PhD students, etc. That lack of representation, what cultural psychologists Stephanie Fryberg and Nicole Stephens (2010) call “American Indian invisibility,” means neither the indigenous or non-indigenous populations are exposed to, or able to internalize, accurate depictions of modern Native American lives and livelihoods.

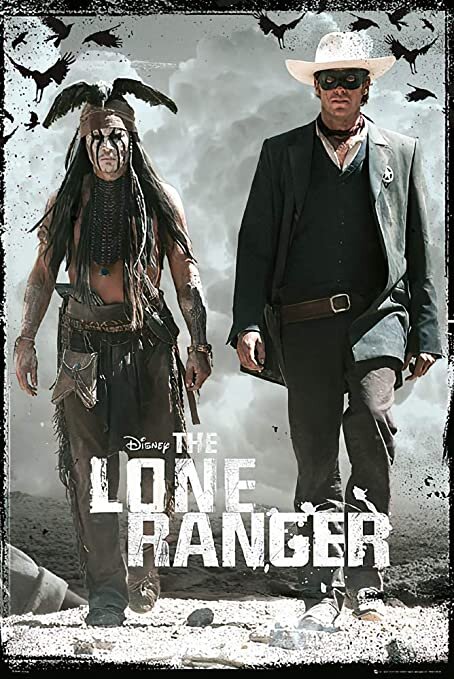

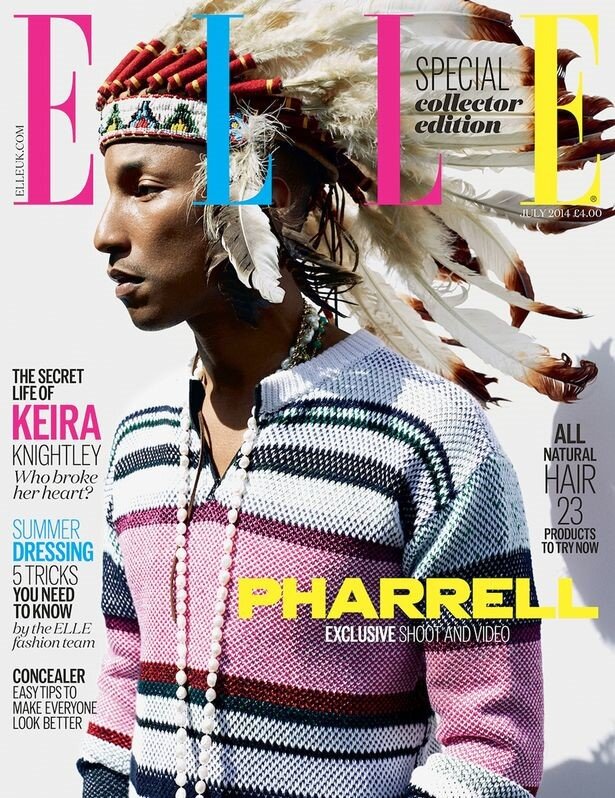

Second, in the absence of accurate representation, mainstream (non-indigenous) media has instead typically presented Native Americans in racist caricatures and stereotypes. Looney Tunes and Disney cartoons, illustrations in books and magazines, wooden cigar shop statues, sports teams names and mascots, live-action films and television shows, and other media have each presented entire generations of Americans with caricatures far removed from the actual lives and livelihoods of contemporary indigenous peoples. One effect is that non-indigenous people come to understand Native American identity both as a racial category and as a cartoonish persona that can simply be “worn” like a hat. Another effect is that indigenous youth not only don’t come to understand that indigenous people thrive as doctors, lawyers, scientists, and so on, but instead are shown that the only “authentic” Indians are the ones with a certain skin tone, who speak the language, who have a mysterious spiritual connection with nature, who live in tipis, who are brave warriors, who wear feathers in their hair, and who are shot dead by cowboys.

The third pattern is that the broader culture is (slowly) starting to become more aware of the problems of the previous two patterns, and is shifting to recognize and represent Native Americans in art—as well as to include and support Native American artists and their creative works. Children’s cartoons, from PBS to Disney/Pixar, are beginning to present more authentic depictions of indigenous characters. I was pleasantly surprised at a modern representation of a Canadian First Nations character on the Amazon television show The Wilds, because it incorporated her culture and identity as it exists in the present day. And Sterlin Harjo’s (Seminole) coming-of-age comedy show, Reservation Dogs, features a group of Native teens living in rural Oklahoma, which is sure to tackle the contemporary American Indian experience and provide the representation of authentic Native culture and identity that we so desperately need.

ISSEP: You’ve attended and presented research at our Existential Psychology Preconferences; how has your experience been with those?

Alexis Goad: It was a fantastic experience! So far I’ve attended the 2020 and 2021 conference. It was so cool to be in a room with people who were focused on such “big questions” about the human experience. In New Orleans [2020], one of my favorite talks was when Roy Baumeister spoke about the issue of “existential agency” given that we each necessarily have to grapple with being in time. This year [2021], I really enjoyed Dr. Louis Hoffman’s presentation about cultural influences on the way science approaches race and identity, as well as Dr. Tomi-Ann Roberts’ Keynote Address about the application of feminist existential psychology in the court—illustrating the tangible ways that existential issues about women’s bodies contribute to sexist laws, and even sexual abuses of women in the criminal justice system, and what to do about it. John Jost's presentation, and all the other presentations, were fascinating too. One of the greatest parts of this field is that it helps build bridges from one topic area to the next; it’s amazing to see how some of the same existential issues course through so many different surface characteristics—from toplessness laws, to faith in economic meritocracy, to your favorite superhero movie. Another great feature of the conference is that the community of researchers is so friendly, and so welcoming, and so supportive—it really is an uplifting community of researchers!

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

“I persevered, adjusted and improved, and kept knocking on doors louder and louder until they finally opened”

Alexis Goad: Persistence is key. As a first-generation undergraduate, I didn’t have a ton of guidance about how to navigate college and get into graduate school. As a result, I got a lot of rejections and didn’t get into any PhD programs the first time I tried. Instead, I had to take a gap year after my undergraduate, volunteered to build research experience, gained more advanced study in a great Master’s program, and then got into a handful of PhD programs. So, four years after I first applied, I did ultimately make it into my current PhD program but only because I didn’t let those early rejections blow me off course—I persevered, adjusted and improved, and kept knocking on doors louder and louder until they finally opened.

So, if you have an interest in the science of existential psychology and it seems out of reach—don’t give up! The institutions can seem daunting and impenetrable, especially to first-generation, women, or minority students, but keep knocking on those doors! It is definitely within your reach and we need your presence.

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the research context?

Alexis played bass all four years she was in the drumline of the Oklahoma State University “Cowboy Marching Band.”

Alexis Goad: I love playing music and have a long history playing various instruments. I started playing drums in the 5th grade and I played up until about 2017 (around the time I embarked for grad school). My initial emphasis was in jazz, with full kits in my school’s jazz band. Eventually I started taking gigs in coffee shops, at community events, and basically anywhere else people wanted us to play. When I played for my high school, it turned competitive and we would travel around to enter jazz festivals and state competitions. In my junior year, we won Oklahoma State Jazz Championships!

Around 7th grade, I also got into marching band and started doing rudimental percussion as part of the drumline. We traveled around to play the sports games, as well as for our own band competitions. I really loved that, and performed through high school and then (after a pretty daunting series of auditions) I made it onto the Oklahoma State University drumline too! I played bass all four years at OSU. Every Saturday, during football season, we performed for about 60,000 people—it was so cool and so much fun!

Now that I’m in grad school, I don’t have any drums but I do play the electric guitar and bass. I also love to cook—totally on board with anything in the kitchen, from the challenge of mastering tried-and-true recipes to the challenges of being creative with food. It’s all so fun and interesting, and I like being able to prepare tasty snacks and meals for my partner and my family and friends (and myself!). In the context of the pandemic, I’ve also become something of a baker, which is new to me as well. I just love learning new things and seeing how it all turns out.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music in the lab; what are you listening to lately?

Alexis Goad: I’m relatively consistent with what’s in my listening rotation and playlists. I’m super into rock, whether it’s grunge, punk, skater, or even some classic/oldies. I really enjoy bands like Nirvana, The Ramones, Radiohead, and Beach Boys. Hozier’s got some good songs, like Jackie and Wilson, From Eden, and In a Week. Green Day is definitely one of my favorites; it feels like I’ve been listening to their stuff my whole life. American Idiot is one of my favorite songs and American Idiot (2004) is one of my favorite albums because it’s actually a “rock opera” inspired by American political events from 9/11, to the Iraq war, to the presidency of George W. Bush.