Gülnaz Kiper on Identity, Difficulty Mindsets, and Hope

Gülnaz Kiper is a PhD Candidate at the University of Southern California (USC). Born and raised in Istanbul, Turkey, she came to America for her undergrad at University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), took a gap year, and then began her Ph.D. training at USC where she works with Dr. Daphna Oyserman. Gülnaz’s research focuses on identity and difficulty mindsets: how they relate to a sense of meaning and purpose in life, finding silver-lining benefits, and behavioral engagement with these experiences.

By Kenneth Vail, Cleveland State University. Feb 27, 2021.

ISSEP: How did you first become aware of and interested in existentialism and existential psychology?

Gülnaz Kiper: I first became aware of the area through the Existential Psychology SPSP Preconference, in Portland, Oregon [2019]. I was deciding which preconference to attend, and it was the most interesting. I asked my advisor Dr. Daphna Oyserman about it, and she said: Yes, Ken and Mark are great, you should totally go to that one. And I’m so glad I did, because I discovered an amazing connection between existential psychology and what I was researching. I’m interested in how identity and difficulty mindsets impact the way people respond to suffering, and the circumstances under which suffering might actually bolster meaning in life, and optimism, and hope about the future.

Most of my life, I’ve grappled with these big questions: Why are we here? Who am I, really? What are our responsibilities toward one another, and toward nature? Why is there so much suffering in the world, what can we do about it? Also, what does it mean that I can even ponder these questions? These questions are fascinating, but they're not just abstract philosophical musings—they have important implications for how we live our lives and how we construct our society. So, it seemed obvious that psychological research on existential issues is not only interesting, but also has practical value.

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some research about how difficulty mindsets impact whether people infer meaning from suffering. How did you develop an interest in that topic?

Gülnaz Kiper: I began to develop this interest through my advisor, Dr. Daphne Oyserman. She developed identity-based motivation theory, which posits that people act in alignment with their most salient identities. Different contexts make different aspects of your identity more, or less, salient. So if you’re in a particular situation that activates your “mom” identity, then that will guide your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Other situations might activate your “psychological scientist,” or your “musician,” or your “rugby player” identity, and each will guide your experiences and motivate your behaviors in unique ways.

Sometimes people interpret difficulty as an occasion for transformational improvement (growth).

The thing that really gripped my attention, though, was that our salient identities also influence how we infer meaning from the difficulties we experience. And there's a bi-directionality there: your most salient identity can impact the way you experience difficulty, and the way you experience difficulty in a certain context can also tell you something about who you are. One area related to this process focuses on what are called “difficulty mindsets,” which is the way that people interpret difficulties—whether obstacles to our goals, or social or physical pain, or other experiences of suffering.

For our purposes here, three mindsets matter most:

First, when people encounter difficulty in a domain that doesn’t seem connected to a salient aspect of their identity, they tend to interpret the difficulty to mean that they’re probably not cut out for this and success is probably impossible. They interpret the difficulty as impossibility, and they give up and move on in search of other things that do seem possible.

Second, when people encounter difficulty in a domain that does seem connected to a salient aspect of their identity, they tend to interpret the difficulty as a relevant signal that success would not simply be a forgettably common or easy accomplishment, but that success would instead be an uncommon, monumental, and noteworthy achievement. In other words, they interpret the difficulty as importance, and they become deeply engaged and strongly committed to the task.

Third, is a rather unique mindset that recognizes the bi-directionality of the process. It recognizes that engaging with difficulty can not only accomplish the goal, but also can potentially lead to positive personal or sociocultural change. When people are in this mindset, when they interpret difficulty as transformational improvement (growth), they lean into the hardest of tasks the with the hope that it will build character and make them more resilient, or help grow their knowledge and skillsets, or change society for the better.

Obviously, these difficulty mindsets are fundamentally connected to existential concerns about “who we are” in any given moment (identity), “what to do” with ourselves (purpose, meaning in life), and how to feel about it (e.g., despair, anxiety, satisfaction, hope).

ISSEP: Are these identity-based difficulty mindsets related to each other?

Gülnaz Kiper: Yes. When we run those correlations, we regularly see the difficulty as improvement mindset is positively correlated with the difficulty as important mindset and negatively correlated with the difficulty as impossible mindset. And that makes sense. If you’re leaning in to difficulty because you think it will lead to improvements, you’re not thinking “this isn’t for me, I should quit”—you’re thinking “this is valuable and good.”

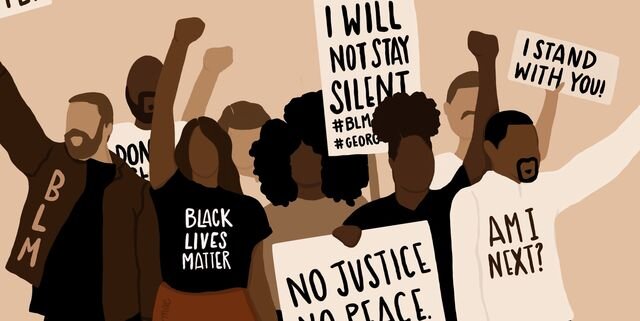

One thing that’s interesting, however, is that although difficulty as importance is often negatively correlated with difficulty as impossible, they can sometimes be positively correlated. So, those mindsets are based on salient identities, but other factors are involved too. For example, if one of my active identities is “Black Lives Matter activist,” then I’d be motivated to support racial equity and equality. When I encounter difficulty in achieving that goal, say due to personal and institutional racism or historical disadvantages, I might interpret the goal as all that much more important to achieve. Thus, I would interpret that difficulty as signaling importance. But I might also look around and recognize the cards are stacked against the movement, and activists have been at it for centuries and yet racial inequality and inequity remain. Thus, I might also interpret that difficulty as impossibility. So, it’s possible to hold importance and impossibility mindsets simultaneously, creating mixed emotions (hope, despair) and complicating one’s commitment (purpose) and behavioral engagement.

ISSEP: Your research also explored the impacts of difficulty mindsets during the COVID-19 pandemic; can you tell us more about that?

Gülnaz Kiper: Yes. Obviously, people are experiencing a lot of suffering and hardship due to the pandemic. So, in my most recent research we assessed people’s difficulty mindsets, their behavioral commitment to stopping the spread, and their perception that there were notable silver linings to the crisis.

Headline image from a “Stop the Spread” campaign, in Pennsylvania, during the coronavirus pandemic.

When people interpreted difficulty as impossibility—perhaps because they thought masks don’t work, or because they thought there was no virus to stop in the first place (e.g., a hoax)—then they disengaged with the virus and the movement to stop its spread. Such participants were less committed to health and safety behaviors, and were less likely to say the pandemic produced some silver linings.

But when people interpreted the difficulties as important and transformative, they engaged fully. They reported greater commitment to stopping the spread, by wearing masks, washing hands and surfaces, and social distancing. They also reported finding more silver linings from the pandemic, for themselves and their communities; they thought they had become a more mature and tolerant person, and that the pandemic exposed social problems (e.g., inequitable racial distribution of high-risk “essential” jobs; access to healthcare) that could now be more directly and urgently improved.

These findings were conceptually interesting, but also have practical value because they highlight, in quantifiable and measurable ways, how the different mindsets can have a strong impact on hopeful engagement with public health recommendations.

ISSEP: Are these identity-based difficulty mindsets an inevitable part of the human experience, regardless of how challenging or privileged one’s life might be?

Gülnaz Kiper: Well, we know they can be situationally-induced, whether it’s in response to the struggle to stop the spread of COVID-19, to achieve racial harmony, or even to solve equations on a middle-school math exam.

The Qatsi trilogy of films produced by Godfrey Reggio and scored by Philip Glass. Left to right: Koyaaniscqatsi: Life Out of Balance (1982); Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation (1988); and Naqoyqatsi: Life as War (2002)

The research on this is still young, so I don’t think we quite know, for sure, whether they’re also simply inevitable, regardless of the comfort of one’s station in life. A variety of philosophers and artists clearly seem to think so. The Qatsi film trilogy is based on the premise that life is struggle, and that life is also the process of overcoming those struggles, and that our efforts to transform the world into a more comfortable space has only created new hardships. That’s a provocative set of ideas. It may indeed be the case that the nature of life is such that people will inevitably, under even the most comfortable circumstances, experience an obstacle (however minor it may be) and devise one or the other particular difficulty mindset. People might even take issue with comfort and pleasure, itself! For example, many people regard luxury and physical pleasure as morally corrupting or spiritually sinful, and may avoid pleasures and/or create physical and social hardships for themselves (e.g., fasting, asceticism, self-flagellation) in an effort to improve their moral and spiritual standing.

One of the most interesting questions I like to think about is whether the difficulty as transformational improvement (growth) mindset might serve a core existential function, framing various aspects of life as a hero’s journey, giving them meaning and significance. When you have to study hard to get into college; when you have to work hard to get the promotion; when you have to live a virtuous life to get into heaven. Those surmountable obstacles can imbue life with hope, giving us a reason to get out of bed in the morning and to fully engage the unfolding cultural dramas of our lives.

“One of the most interesting questions I like to think about is whether the ‘difficulty as growth’ mindset might serve a core existential function, framing various aspects of life as a hero’s journey, giving them meaning and significance.”

ISSEP: You’ve been studying these issues using psychological science. Do you see the topic being dealt with in interesting ways in the humanities or the arts?

Clockwise from top left: No mud, no lotus: The art of transforming suffering (2014); Finding the gold within (2014); and Suffragette (2015).

Gülnaz Kiper: One place I see it is in a beautiful poem called “In a Dark Time,” by Theodore Roethke. My favorite lines are:

“What’s madness but nobility of the soul

At odds with circumstance? The day’s on fire!”

In a similar vein is a book called No mud, no lotus: The art of transforming suffering, by a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh. It explores the “difficulty as improvement” mindset, and it contains some provocative passages, for example:

“The main affliction of our modern civilization is that we don't know how to handle the suffering inside us, and we try to cover it up with all kinds of consumption” and “…without suffering, there's no happiness. So, we shouldn't discriminate against the mud. We have to learn how to embrace and cradle our own suffering, and the suffering of the world, with tenderness.”

Basically, the idea is that sometimes the greatest satisfaction with life comes from overcoming the greatest obstacles—that sometimes the most beautiful things in life stem from some of the ugliest—just the way the lotus flower stems from the mud.

I also recommend a documentary called Finding the Gold Within (2014). It follows six young Black men in Akron, Ohio, over the course of 3.5 years. They’ve got some serious obstacles in their lives, but they’ve also been mentored for seven years by a group of older men, who play music and teach them stories and myths about suffering and how to understand and navigate obstacles in life. That mentoring prepared them to stay strong and overcome the world’s challenges.

In a more artistic lane, I recommend the film Suffragette (2015). It's about the movement for women’s rights to vote, which was an uncertain goal that might have taken months, decades, or centuries to achieve, if at all. It illustrates all three difficulty mindsets (difficulty as impossibility, as importance, as improvement), under various circumstances, and how those mindsets impacted the activists’ sense of purpose, meaning in life, and behavioral commitment to the movement.

ISSEP: What do you think are some of the remaining issues in studying the ways that difficulty mindsets can help people see the silver linings in hard times?

Gülnaz Kiper: Mainly, to continue exploring whether and how the difficulty as importance and as improvement mindsets might serve the existential function of imbuing life with meaning and significance.

Another interesting area would be to learn more about the social value of the various difficulty mindsets. Other people’s difficulty mindsets seem like important information, and the value of each mindset might depend on the situation at hand.

We might place low value on others who adopt a difficulty as impossibility mindset because they represent a social liability. Indeed, we hear the phrases “why should I help you, if you’re not going to help yourself” and “nobody likes a quitter” in domains from sports to business, potentially because quitters might waste our own social capital or jeopardize our own goals. On the other hand, as Kenny Rogers sang in The Gambler, blind persistence can also be a problem and sometimes the hero of the story needs to know when to fold up and move on.

On the other end of the spectrum, we might value those who tend to adopt the difficulty as importance and as improvement mindsets because they go the extra mile for the people they care about and stand up for what they believe in, and they lean in to adversity to achieve their goals and make the world a better place. We might want to be close to these personal heroes, whether as family or friends or romantic partners, because we can trust that they’ll support us even through the hard times. And we might want them in our communities, because they’ll give their blood, sweat, and tears to help improve our lot.

“I’ve attended the XP preconference for the past three years—I love it!”

ISSEP: You’ve attended, and presented research at, our Existential Psychology Preconferences. What’s been your experience been with those events?

Gülnaz Kiper: I've attended the XP preconference for the past three years—I love it! Each time it’s been so fascinating. I enjoy the presentations, and seeing other researchers interested in the “big questions” of life. This year, my favorite talk was the Special Address, by Tomi-Ann Roberts, about objectification of the female body and sexism in the law. That was a highlight for me. Outside of the talks, my favorite part at each preconference has been interacting with everyone. Even this year, we had that virtual happy hour, which I thought was very, very enjoyable. I got to connect with friends and meet new people. It was great. I’d recommend that if anyone goes to SPSP, they should go to the existential psychology conference—it's just very enriching.

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

“talk to people, read widely, and learn about cultures past and present”

Gülnaz Kiper: Learn the research literature, and the methods, but don’t get academic tunnel-vision. Stay connected to the world; be aware of what's happening, and how people are experiencing and participating in what's happening. Follow the news, and remember that whatever you’re studying in the psych lab—the arts and humanities probably got there first, so build on their insights and bring science to bear on it. So, talk to people, read widely, and learn about cultures past and present… then you can address the question: Why are people behaving this way?

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the research context?

Gülnaz Kiper: Well, I was living at USC, in Los Angeles. But when the pandemic began, I put everything in storage and left to be with my family here in Istanbul. I’m working and studying remotely, like everyone else, but family is important and mine is here in Turkey.

We’ve also been caring for some stray cats here. In Istanbul, we have so many stray cats, I cannot begin to tell you. But people take care of them; they are always fed and treated well. There are four that have adopted us, and they’re so cute. I’ve named them Kobe (after Kobe Bryant), Kaju, Juni, and Şapişik. I love them, so we’re a cat family now.

Other than that, I like to cook and try creative new recipes. And I like to travel, meet new people, and visit new places, but haven't done that since the pandemic started.

I’ve also been singing for quite some time, and I'm super into it. Other people seem to like it when I sing, but also it just uplifts me. It puts me in a totally different vibe and mindset than when I'm focused and working; much more intuitive and emotional, rather than analytic and cognitive. I can just relax and have fun with it. I like to sing musical songs, and Disney songs make be so happy. Lately, I've been doing two. One is from Lion King (1994), titled I Just Can't Wait to be King. The other one I love to sing is called Into the Unknown, from Frozen 2 (2019). In the film, the character Elsa sings it, and it's about a mysterious siren calling her to come into the unknown. She's hesitant about it, and contemplates her ambivalence about going out into the unknown and discovering who she really is. It’s an uplifting way to engage with fear, self-discovery, and personal growth.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music in the lab; what are you listening to lately?

Gülnaz Kiper: When I’m working, I love to listen to film score soundtracks. I usually switch between Lord of the Rings soundtrack, Harry Potter soundtrack, or Hans Zimmer's Blue Planet. Such good albums for study and work; they’re low on lyrics, with really rich music—great for keeping focused.

When I’m not working, I like to listen to a variety of music. Moonchild did a great NPR Tiny Desk Concert appearance that I return to often. I also love Spanish songs, Portuguese songs, Bossa Nova, and I love some jazz. One Spanish song that I've been recently obsessed with is called Soledad y el Mar, meaning Solitude and the Sea, by Natalia Lafourcade. Beautiful song and lovely music video.